The Power of Perseverance: My Story of Triumph

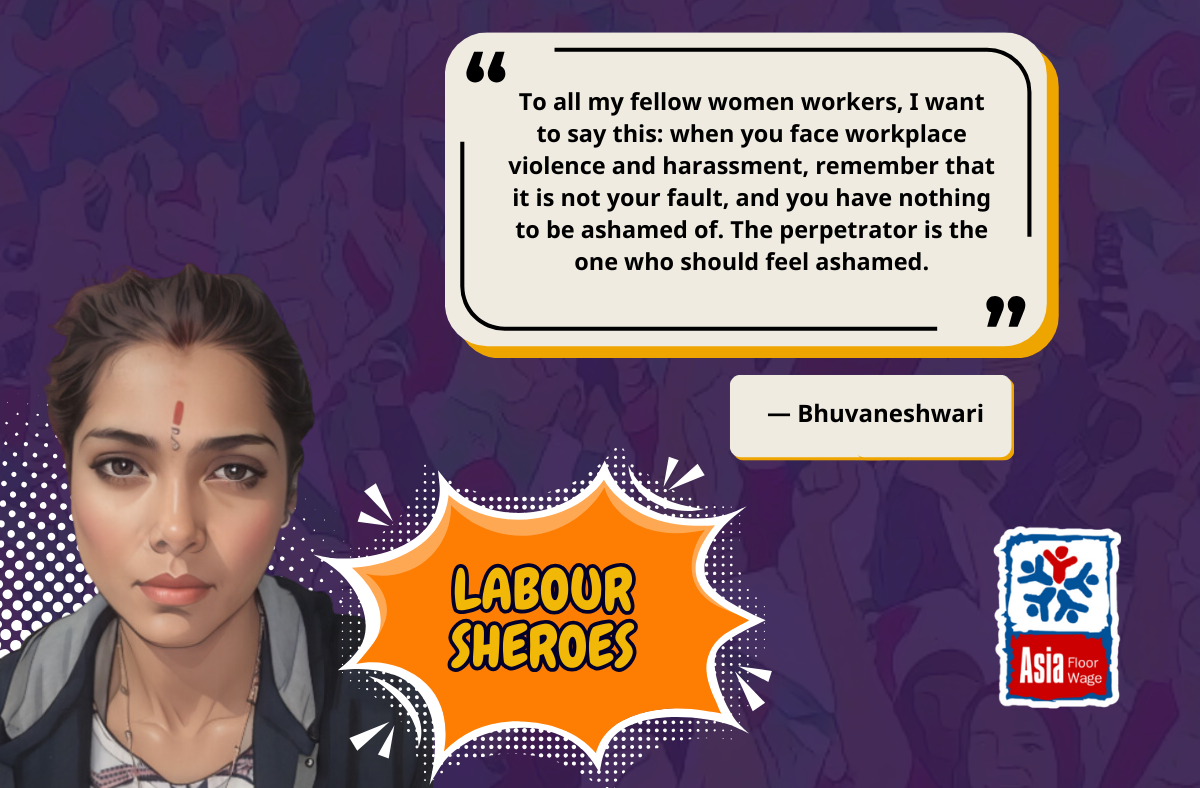

By Bhuvaneshwari

Bhuvaneshwari's journey is a testament to the power of resilience, courage, and the unbreakable bonds of family and community. Born and raised in the small town of Kodiyal in Karnataka, she faced numerous challenges from a young age, including financial hardships, a difficult marriage, and workplace violence. However, with the unwavering support of her mother and the guidance of her union leader, Nagarathna, Bhuvaneshwari found the strength to overcome these obstacles and emerge as a powerful advocate for the rights of women workers. Her story is one of transformation, hope, and the courage to turn fear into strength.

-

Born and raised in the small town of Kodiyal in Mandya District, Karnataka, I am one of three siblings - an older sister, myself, and a younger brother. Our father worked tirelessly to support our family, juggling between tailoring work during the day and security guard duties at night. His hard work and dedication allowed me to pursue my education until the 10th standard, and life became a little more comfortable when my brother started working and contributing to the family income.

At the age of 20, my parents arranged my marriage, spending Rs. 5 lakhs on the ceremony. However, my married life was far from happy. I have a stammer, and my husband, and his sister, constantly persecuted me. After enduring two years of hardship, I made the difficult decision to leave my husband and return to my parents' home in Bangalore. It was my mother's unwavering support and love that gave me the strength to forge a new path for myself and my 4-year-old son, whom she now cares for while I work to support us.

With encouragement from a neighbor, I began working at a garment factory as a checker. Though I briefly left this job to assist with my sister's wedding preparations, I soon found employment at Shahi 8 as a feeding helper. It was there that I faced one of the greatest challenges of my life. After a few months, my supervisor began subjecting me to verbal and sexual abuse. I suffered in silence until I met Nagarathna, the President of the Union. Her support and guidance helped me gain the confidence to file a complaint with the Internal Committee (IC).

Pursuing the complaint was not easy, as my co-workers distanced themselves from me, disapproving of my actions. However, with the union's support, I found the strength to persevere and appear for the inquiry. When the management finally terminated the abusive supervisor, I felt a sense of relief and pride. Now, I use my experience to help other workers, taking them to Union representatives whenever I witness misconduct or abuse. I am confident in my ability to face any challenge in the factory with courage.

Throughout my journey, my mother has been my rock. When neighbors pressured her to send me back to my husband, she stood firmly by my side, offering me unconditional love and support. Nagarathna, too, has played a crucial role in my growth, teaching me how to face workplace challenges head-on. Inspired by her empathy, I am now an active participant in union activities, fighting for the rights and justice of my fellow workers.

My dreams for the future are simple yet meaningful. I aspire to provide my son with a good education and to take care of my aging parents. In my free time, I find joy in listening to Kannada film songs and teaching my son to read, while also helping my mother with household chores.

To all my fellow women workers, I want to say this: when you face workplace violence and harassment, remember that it is not your fault, and you have nothing to be ashamed of. The perpetrator is the one who should feel ashamed. By joining the union, I found the strength to fight for my rights and emerge victorious. As women, we possess immense strength, and we must learn to transform our fear into courage.

My journey has not been easy, but it has taught me invaluable lessons about resilience, courage, and the power of unity. As I continue to navigate life's challenges, I draw strength from the unwavering support of my mother and the solidarity of my fellow union members. Together, we will continue to fight for justice and build a better future for ourselves and generations to come.

-

Bhuvaneshwari’s story is part of 'Labour Sheroes,' an initiative under the 16 Days of Activism campaign by Asia Floor Wage Alliance. Through this series, we share the stories of women garment workers from South and Southeast Asia who are breaking barriers, fighting against workplace violence and harassment, and leading the change for better working conditions in the global garment industry.

The Dindigul Agreement at Two Years: A Milestone in Garment Industry Transformation

Two years ago, a tragic event shook the garment industry in Dindigul, India, leading to a groundbreaking movement to end gender-based violence and harassment (GBVH) in the workplace. The #JusticeforJeyasre campaign, ignited by the sexual assault and murder of 21-year-old Jayasre Kathiravel by a male supervisor, culminated in the establishment of the Dindigul Agreement—a legally binding agreement among global fashion brands, suppliers, and unions. This agreement has since become a model for eradicating GBVH, enabling women's agency, and fostering an ethical and equitable work environment in the world of work.

by Sinduri Sappanipillai, Asia Floor Wage Alliance (AFWA)

Lakshmi*, a worker at the Eastman Exports factory in Dindigul, greeted us with a smile that spoke volumes about the transformative power of the Dindigul Agreement. Having worked in the garment industry for over a decade, Lakshmi now engages with her supervisors confidently—a stark contrast to the fear and intimidation that once pervaded the workplace. "We used to see them with fear, but everything changed after the Dindigul Agreement. Now, we look them in the eye and answer confidently," she said.

The Genesis of the Dindigul Agreement

Signed in 2022, the Dindigul Agreement is the first enforceable brand agreement (EBA) in India and a historic milestone in the Asian labor movement. It brought together the Tamil Nadu Textile and Common Labour Union (TTCU), Eastman Exports, Asia Floor Wage Alliance (AFWA), and Global Labor Justice (GLJ), and major global brands like H&M Group, Gap Inc., and PVH Corp. This coalition aimed to create a world of work free from violence and harassment, with a specific focus on the garment industry.

The agreement covers over 3500 workers at Natchi Apparel and Eastman Spinning Mills, the majority of whom are Dalit women. Many of the workers are also young migrants who live in company-owned dormitories and have faced severe discrimination and abuse. The Dindigul Agreement's comprehensive approach, rooted in international labor standards like the International Labour Organization's (ILO) C190 and R206, takes into account women's agency in grievance handling and remediation; as well as ILO #C87 and #98 on Freedom of Association. It also aligns with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) guidelines and India's 2013 Prevention of Sexual Harassment (POSH) Act, making it a model for implementing international labor standards in the workplace.

Groundbreaking Mechanisms for GBVH Prevention

The Dindigul Agreement introduced the AFWA Safe Circle approach, a worker and union-led training, monitoring, and remediation program. Worker Shop Floor Monitors (SFMs), trained by TTCU, play a critical role in this system, helping co-workers report GBVH and facilitating regular meetings with management to resolve issues. This proactive approach has led to a significant reduction in GBVH incidents, with 98% of the 185 grievances raised in the first year being resolved, including all 23 GBVH cases.

Read the first year progress report here.

Latha*, a shop floor monitor, highlighted the effectiveness of this system: "Women workers now come forward and share their problems with us, knowing we are here to listen and provide solutions. Any small issue is usually resolved within a few hours. If there's something we can't solve, we bring it to management and ensure it is resolved within 2-3 days."

The agreement has catalyzed profound cultural and behavioral changes in the workplace. Mid-managers and supervisors have significantly altered their behavior towards workers, fostering a more respectful and inclusive environment. This shift has not only improved worker relations but also led to a notable reduction in the factory's attrition rate by 67% between 2021 and 2022, benefiting both workers and business operations. A detailed report of the second year's progress is underway.

The impact of the Dindigul Agreement extends beyond factory floors, contributing to the global effort to eliminate GBVH and other rights violations by enabling women to actively address and prevent instances of GBVH. Women workers in their testimonies share how they found the courage to confront and prevent instances of GBVH in their workplaces, transport facilities, hostels, and communities.

Strengthening FOA and Grievance Mechanisms

Recognizing the essential role of Freedom of Association (FOA) in preventing GBVH, the agreement explicitly protects workers' rights to form and join unions. This protection has enabled workers to speak out and report grievances without fear of retaliation, ensuring timely and effective resolutions.

Thenmozhi*, a quality checker at the factory, emphasized the importance of this support system: "Earlier, we were scared, fearing trouble and retaliation for speaking out. But now, we have a support system. We can go to SFMs for any issues, and they resolve them for us. We also have the Internal Complaints Committee (ICC) now. The agreement has helped us understand our rights and has made us confident."

Recommendations for Brands:

Each signatory and stakeholder in the agreement has made measurable and visible contributions:

- AFWA and GLJ have been instrumental in guiding and directing both the union and supplier to ensure the agreement's implementation.

- TTCU has supported SFMs, enabling them to address workers’ concerns and grievances on the shop floor. TTCU also actively engages in resolving worker issues through union-management dialogue.

- Eastman has ensured compliance with remediation efforts and the implementation of corrective action plans.

- Independent Assessors have been involved in strengthening the ICC and ensuring the grievance mechanism is effectively in place.

Going forward, here are some recommendations for brands to take a more visible and active role in the agreement process. They should reward suppliers like Eastman, where worker unions are accepted, and where grievance mechanisms have had unprecedented success in GBVH-related grievance remediation. By prioritizing orders from factories that uphold worker-friendly practices, brands can support and incentivize ethical workplace practices. This visible commitment will send a strong message of support for worker rights and protections, demonstrating a genuine global effort to safeguard worker-driven grievance mechanisms and promote an equitable work environment.

A Call to Action for Global Brands

The Dindigul Agreement has proven to be a transformative model for eradicating GBVH. Its positive impact over the past two years has helped to strengthen workers’ rightful voice at work and fostered a more stable and ethical supply chain. This landmark agreement highlights the need for more brands to support its expansion and replication, ensuring a safe and equitable workplace. The tragic murder of Jeyasre Kathiravel underscores the urgency for such protections, and the agreement's success proves that the industry can evolve for the better, and safeguard the dignity and rights of every worker.

*To protect the privacy of certain individuals, names and identifying details have been changed.

Nike Shareholders Lack ‘Just Do It’ Energy

Written by Jasmin Malik Chua for Sourcing Journal (12 September 2023)

Nike shareholders voted against a proposal that would have required the company to oversee and report on the effectiveness of its supply chain due diligence efforts in alignment with its equity and human rights commitments. The resolution, filed by activist investment platform Tulipshare, also called for Nike to disclose the metrics used to monitor forced labor and wage theft risks, consider adopting American Bar Association human rights contract clauses, and assess if these findings led to policy changes.

Tulipshare's communications manager, Samuel Collins-Charles, criticized Nike for not providing sufficient analysis regarding its steps to address alleged Uyghur forced labor in its supply chain. He also mentioned ongoing labor disputes, including a complaint filed in March accusing Nike of violating OECD guidelines for responsible business conduct by failing to address wage losses among garment workers during the pandemic.

Workers' rights organizations like the Asia Floor Wage Alliance and the Global Labor Justice-International Labor Rights Forum filed a complaint, joined by 20 garment sector unions across several countries, alleging that Nike owes workers $1.4 million in unpaid wages in Cambodia and $28 million elsewhere. They claim that instead of compensating workers or investing in safety and productivity programs, Nike engages in buyback schemes to artificially boost its stock price. The complaint also noted that Nike did not engage with garment worker unions, as expected by OECD guidelines and despite union requests for dialogue.

Read the full article here.

Garment Workers in Asia Need ILO Convention 190

“Ijah, you know, right, if you take maternity leave, your contract will expire? So don’t even think of taking maternity leave," said the factory supervisor one afternoon when Ijah was about to leave her line to rest.

"I don't understand, ma'am. You cut my wages and my menstrual leave compensation after my pregnancy started showing,” Ijah cried, frustrated that she wasn’t even getting to rest during her pregnancy. However, the supervisor insisted that Ijah wouldn’t be able to take her maternity leave because her contract would expire. Indonesia’s labor law stipulates three months of maternity leave, but Ijah’s contract would have ended by the time she is due.

Ijah has been working as a contract worker since she was a young woman in the Cakung Industrial Area in North Jakarta, Indonesia. She is now 35 years old, married with two children and a third on the way, and still hasn’t received ‘permanent worker’ status.

This is due to a common but illegal practice in Indonesia's garment industry where factories frequently hire workers for no longer than three months at a time. Consequently, employees like Ijah are forced to move from one factory to another without severance pay, often working anywhere from 30 days to 3 months at each location. A significant number of these workers are women who, consequently, are forced to forfeit essential social security benefits such as menstrual and maternity leaves. Ijah, like many others, can only hope her contracts are repeatedly renewed until she gets old and weary.

When fashion companies in the Global North started to look for labor markets in the Global South, the garment sector was positioned as a promise of economic and social upliftment for millions across Asia. However, the industry has become a hotbed of gender-based violence and harassment (GBVH), particularly for women. A recent global International Labour Organization (ILO) study found that 22.8% or 743 million persons in employment had experienced at least one form of violence and harassment at the workplace. While data on sexual violence is scarce, more so at the regional level, available studies indicate particularly high rates in some countries.

In 2021, the ILO Better Work program reported that approximately four out of every five workers in Indonesian factories expressed concern about sexual harassment at work. In the same study, 42.5% of women workers from Myanmar said they had been sexually harassed at work. In Vietnam, 19.8% of female workers and 11.9% of male workers reported that they had experienced at least one form of violence in the previous six months (CARE International 2020).

C190: Promise of a safe work environment

The ordeals that Ijah and countless other garment workers have to endure, day in and day out, teeter on the line of outright violence and incessant harassment. It is a stain on human rights that such flagrant violations persist globally, not only in the workplace but also in homes and public spaces. The cost is not just economic; it seeps into the very fabric of our societies, burdening individuals, families, and entire communities. The bleak reality is that these abuses persist, unchecked and unimpeded, despite their clear illegality, with emboldened perpetrators taking advantage of the fear of the most vulnerable of workers.

Everyone is entitled to a workplace where dignity and safety aren't mere luxuries but inherent rights. This includes freedom from violence and harassment of any kind, especially when it's gender-based.

Recognizing this right as paramount, the ILO, in June 2019, adopted the first international treaty on workplace violence and harassment – Convention 190 (C190) and its accompanying Recommendation 206 (R206). The treaty came into effect on 25 June 2021.

Governments pledging support to C190 have a duty to enact necessary laws and policies to counter and eliminate workplace violence and harassment. The treaty rightly identifies women and other vulnerable groups as being at an escalated risk of these rights abuses – a reality that is particularly acute during times of crises, like a global pandemic. It thus calls for an inclusive, gender-sensitive, and integrated approach to put a definitive end to all forms of violence and harassment at work.

C190 and R206 represent a historic chance to mold a future of work that is rooted in dignity and respect for everyone. But, even two years after its inception, the journey to realizing safe and GBVH-free workplaces remains daunting. It's disheartening that in Asia, not a single country has embraced C190 and R206. Local laws may exist on paper in these nations, promising protection to workers, but they're routinely overlooked or breached – all for the sake of productivity and profit.

Let’s take a quick look at the state of affairs in some of the major garment-producing markets in South and Southeast Asia.

Indonesia:

Between 2020 and 2021, the Central Board of Serikat Pekerja Nasional (SPN), Lembaga Informasi Perburuhan Sedane (LIPS), and the Workers' Rights Consortium (WRC) conducted a study of 12 garment supplier factories in Java Island and found that the most prevalent types of GBVH included:

- Verbal violence (yelled at, rudely called, insulted, threatened, asked out to date, seduced, sexual chat)

- Physical violence (hit, kicked, grabbed, thrown, poked with fingers, touched, hugged, peeked at, buttocks grabbed, bra straps pulled)

- Other forms of violence such as physical punishment, increasing production targets or working hours, and withholding maternity leave and menstrual leave

Although the study doesn’t give sexual violence its own category, under the definition given by ILO C-190, actions like ‘asked out to date, seduced, sexual chat’ and ‘poked with fingers, touched, hugged, peeked at, buttocks grabbed, bra straps pulled’ would constitute forms of sexual violence.

“GBVH is corrosive to women workers’ sense of self and makes them voiceless and powerless, while also becoming a barrier to their accessing other fundamental rights such as freedom of association and living wage,” says Sumiyati, Chair of SPN Women’s Committee and member of AFWA Women’s Leadership Committee (WLC). Fashion brands must make concrete commitments to understanding and addressing risk factors for GBVH across their supply chains through a ground-up approach that upholds respect for freedom of association and is led by workers and trade unions (AFWA, 2021). Sumi continues, “Factories need to be converted into GBVH-free zones, but workers cannot do this alone.”

Sri Lanka

GBVH prevalence in Sri Lankan workplaces stems from patriarchal norms, power imbalances, gender equality ignorance, lax policy enforcement, and insufficient victim support. These issues are exacerbated by hierarchical work structures where those in power exploit their authority. Although the government has legislated protections such as the Employment of Women, Young Persons, and Children Act, the Penal Code, and the Sexual Harassment Act, their enforcement is often inconsistent.

A 2021 study by AFWA on GBVH during the COVID-19 pandemic found that many young mothers had been forced to resign after the factory they worked in refused to reopen the creche. Many others had to leave their children in their village homes, to be cared for by elderly parents, while they went to the city for work.

Various NGOs, trade unions, and civil society groups in Sri Lanka are actively working to combat GBVH by raising awareness, offering victim support, advocating policy changes, and promoting gender equality through training and capacity building. Efforts to foster safe, inclusive work environments via gender-sensitive policies, awareness campaigns, and stakeholder training are underway.

Cambodia

In 2019, the Garment, Footwear, and Travel Goods sectors contributed 57% to Cambodia's total exports and employed 808,223 workers, 80% of whom were women. These workers, primarily rural migrants, often endure substandard living conditions in city rentals marked by poor hygiene, high costs, and low security. Despite their significant presence in these industries, female workers face hardships due to their limited education and societal norms. The persistence of male dominance, particularly in higher positions within factories, further exacerbates their plight.

A 2021 study by AFWA found that Cambodian workers were too afraid to take bathroom breaks for fear of verbal abuse if their daily production targets were not met. They would limit themselves to a single break per day, hold in their urine for a long time, or even restrict water intake, despite being aware of the risk of urinary tract infections or suffering regular stomach and bladder pain.

In another instance, all workers received less than half of the monthly minimum wage when work was suspended after brands cancelled or reduced orders during the pandemic. Women workers were disproportionately impacted by the illegal wage deductions and didn’t even receive the monthly US$70 mandated by the government.

India

India's struggle with gender inequality and violence against women extends into workplaces, particularly the female-dominated garment industry. Fear of backlash, social stigma, and unawareness of their rights often discourages victims from reporting harassment, perpetuating a culture of silence.

Several legislative measures exist to combat these issues:

- The Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace Act (POSH), 2013, mandates safe working conditions and complaint-handling mechanisms.

- The Factories Act, 1948, establishes health and safety standards in garment factories.

- The Maternity Benefits Act, 1961, provides protections for pregnant and new mothers.

- The National Policy for Women, 2016, aims to tackle gender disparities and foster safe work environments.

However, enforcement gaps and patriarchal attitudes hinder the effectiveness of these laws. Various government bodies, NGOs, and industry stakeholders are working to raise awareness and increase sensitivity towards these issues. More recently, increasing emphasis has been placed on addressing workplace GBVH, including in the garment industry. At the same time, greater effort needs to be put into creating safe and inclusive environments for women, strengthening law implementation, and promoting gender equality.

One successful effort towards this is the Dindigul Agreement to Eliminate Gender-based Violence and Harassment. In April 2022, Indian women- and Dalit-worker-led union TTCU signed a historic agreement with clothing and textile manufacturer Eastman Exports to end GBVH at Eastman Exports’ factories in Dindigul, in the southern state of Tamil Nadu in India. TTCU, GLJ-ILRF, and AFWA also signed legally binding agreements with multinational fashion companies and their supplier to build a safe and GBVH-free workplace or impose business consequences on the supplier in the case of violations. Enforceable brand agreements, in which multinational companies legally commit to labour and allies to use their supply chain relationships to support a worker- or union-led program at certain factories or worksites, have proven effective in holding brands and suppliers accountable for workplace safety.

Vietnam

Vietnam legally prohibits violence, including sexual harassment, both at home and work. This is enshrined in the Domestic Violence Prevention and Control Law of 2007 and the 2012 Labour Code, which explicitly bans workplace sexual harassment.

However, the National Study on Violence Against Women in 2019 found that 62.9% of women had experienced at least one form of physical, sexual, emotional, and economic violence, and controlling behaviors by their husbands in their lifetime; 31.6% had experienced the same in the previous 12 months. In addition, the study showed 13.3% of women suffered sexual violence by a husband/partner in their lifetime and 5.7% in just the last 12 months.

There is no specific data on violence, including sexual violence, and harassment at the workplace, but some experts believe it to be higher than the 23% stated in a 2022 ILO study. Gaps in the policy and in its implementation and enforcement as well as the deeply ingrained patriarchal culture are among contributing factors to the problem.

In an article published in March 2023 by the Vietnam General Confederation of Labour (VGCL) mouthpiece, a representative said that the country should review and pass the ILO C-190 because it would act as a foundation for any policy to eliminate violence and harassment, including GBVH, at the workplace.

Pakistan

Pakistan's garment industry is the country's second-largest employer, providing jobs for 15 million people, accounting for 38% of its manufacturing labour force, 8.5% of its GDP, and almost 70% of its exports. Around 20% of the country’s garment factories produce readymade garments for US and European markets. A significant number of garment workers are women, who face numerous challenges including pay disparity, limited leadership opportunities, and pervasive GBVH. In 2022, Pakistan was ranked 145 out of 146 countries in the World Economic Forum's global gender gap report, making it the second worst in gender parity.

In 2010, Pakistan introduced the Protection against Harassment of Women at the Workplace Act, necessitating every organization to have an Internal Complaints Committee (ICC) for handling complaints linked to GBVH, but implementation gaps persist due to systemic issues, structural inequalities, cultural norms, inadequate worker awareness, inadequate training for ICC members, fear of employer retaliation, and mistrust in the justice system. In 2022, the act was amended, expanding the definition of workplaces to both formal and informal settings and strengthening protections for victims of sexual harassment, including ensuring confidential reporting mechanisms, protection against victimisation or retaliation, and access to support services such as counselling and legal aid.

These recent amendments reflect a commitment to strengthening the legal framework surrounding sexual harassment in Pakistan but successful implementation depends on collaborative efforts from all stakeholders and continued vigilance to ensure safe and inclusive working environments, especially for women.

Bangladesh

The garment industry in Bangladesh is one of the largest in the world, employing millions of workers, a majority of whom are women. Unfortunately, these workers are vulnerable to various forms of gender-based violence, including sexual harassment, assault, and exploitation. The Bangladesh government has recognised the severity of GBVH in the workplace and has taken legislative measures to address the issue:

- The Bangladesh Labor Act (2006): This law defines sexual harassment and outlines procedures for filing complaints and conducting investigations in workplace harassment cases in all sectors, including the garment industry.

- The Bangladesh Labor Rules (2015): These rules supplement the Labor Act and require employers to establish appropriate mechanisms, such as complaint committees, to handle complaints effectively.

- National Tripartite Plan of Action (NTPA) on the Elimination of Violence against Women and Children in the Workplace: The government, in collaboration with worker and employer organisations, developed the NTPA to address create safe working environments, raise awareness on GBVH, provide support services, and strengthen legal and policy frameworks.

Despite these measures, implementation and enforcement of existing laws and codes of conduct are inconsistent and there is limited awareness among workers about their rights — the lack of available mechanisms for reporting further compounds the problem.

Lack of worker-led initiatives increases the risk of GBVH

To prevent and eliminate GBVH, freedom of association is absolutely necessary. Survivors of GBVH often refrain from reporting incidents or accessing grievance redressal mechanisms due to fear of retaliation or lack of trust in the management, and worker-led labor unions protect workers from such backlash.

Not only have fashion brands’ voluntary codes of conduct and corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives failed to ensure GBVH-free workplaces, their purchasing practices have increased the risk of GBVH. The garment global supply chain is structured such that brands have all the market power. They do not produce garments, they source their products from companies and factories, normally in low- and middle-income countries. Business relationships between brands and suppliers are governed by purchasing practices that impact the functioning of supplier firms and, in turn, working conditions in these firms. As a result, brands are able to pressurise suppliers to reduce costs and increase production targets. This high-pressure model leads to an environment where bullying and GBVH are used as tactics to speed up production and discipline workers, while also deterring them from joining unions and reporting labour violations.

The absence of brand governance and accountability in preventing and eradicating GBVH in garment factories has led to crippling debt and hunger for women workers due to insecure employment and wages. This financial instability exacerbates their already significant burdens, intensifying the violence and harassment they encounter both at work and at home.

To counter these governance gaps within global garment supply chains, AFWA has collaborated with trade unions to devise a joint employer liability legal strategy, which targets brands that evade legal responsibility for harmful purchasing and other practices that foster conditions conducive to GBVH in their supplier factories.

The need for C190

While existing laws partially address GBVH, they often fall short of the standards set by ILO's C190, with a limited scope and emphasis on punishment over prevention. Enforcement is weak and doesn't extend to temporary or contract workers (in the informal category of workers), including those working from home. Ratifying and implementing C190 and R206 would bolster legal frameworks, compelling countries to provide comprehensive remedies for survivors, including all workers, even those commuting or migrating for work. Importantly, this legislation also recognises the relationship between domestic violence and workplace concerns.

C190 fosters gender justice and empowers women by protecting them from violence and harassment, enabling them to participate actively in unions and report incidents confidently. Both C190 and R206 recognise economic harm as violence, offering a gender-inclusive approach to addressing workplace violence. It specifically looks to address risks from discrimination, power imbalances, and occupational health and safety issues.

Labour and feminist movements must unite to push for the ratification of ILO's C190 and R206. Trade unions can use these guidelines in collective bargaining and enforceable agreements with suppliers and brands to implement worker-led prevention of GBVH, as seen in instances like the Dindigul Agreement in Tamil Nadu, India.

Existing policies protecting workers’ rights are often weak and inconsistent. Brands exploit these gaps, frequently changing suppliers for cost benefits. To compete for orders, countries sometimes overlook worker benefits, necessitating a regional approach to worker protection. C190, the first international labour standard offering a framework to tackle workplace violence, including GBVH, is essential. It legally recognises the right to a violence-free workplace and sets out the obligation to respect, promote, and realise this. C190 encourages international cooperation and knowledge exchange, contributing to global women worker protection. Hence, we call for countries to ratify ILO's C190. Everyone is entitled to a workplace where dignity and safety aren't mere luxuries but inherent rights.

How Gender-Biased Minimum Wage Harms Women Workers in Indonesia

Co-authored by Dian Septi Trisnanti, President of Federasi Serikat Buruh Persatuan Indonesia (FSBPI) union and Ranjana Sundaresan, Asia Floor Wage Alliance (AFWA)