Day Eleven Of The Worker Action Delegation | Holding Nike To Account In DC

June 6, 2025Worker Action Delegation

June 5, 2025

On the last day of the Worker Action Delegation, Leni, Dedeh, and Dinar brought the demands of Asian garment workers to the heart of U.S. political power. In Washington, DC, they met with U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders to share firsthand accounts about how workers in Nike’s supply chain are treated. The meeting underscored the need for global brands to be held accountable for labor violations they continue to deny. After hearing from the workers, Senator Sanders called Nike’s actions “corporate greed at its worst.”

Garment workers who make @Nike billions deserve living wages and human rights. Thanks @SenSanders for supporting the Fight the Heist campaign.

Proud to stand with workers, unions @asia_floorwage in this fight #SeeUsNike https://t.co/Peh0lD94ek

— Global Labor Justice (@global_labor) June 6, 2025

This final stop marked the conclusion of a powerful journey that began in Oregon and moved through New York and Philadelphia. At every stage, the workers challenged the Nike's public image and exposed the reality behind its profits—wage theft, union-busting, and gender-based violence and harassment. Their message across cities was clear: garment workers will no longer be ignored by brands that profit from their labor.

As the tour closes, its significance extends beyond any single event. The voices of Dedeh, Leni, and Dinar have reached new audiences, built new alliances, and strengthened a transnational call for justice. Across Asia and around the world, thousands of garment workers and their allies are demanding what workers are rightfully owed. The Worker Action Tour may have ended in Washington, but the movement it helped grow is only gaining momentum.

Stay tuned for more updates and read: Day Ten Of The Worker Action Delegation | Worker Activists Speak from Capitol Hill

Day Ten Of The Worker Action Delegation | Worker Activists Speak from Capitol Hill

June 6, 2025Worker Action Delegation

June 5, 2025

On Day Ten of the Worker Activist Delegation, Leni, Dedeh, and Dinar brought the voice of Asian garment workers directly to the U.S. capital—a global center of policymaking, federal legislation and movement building. At a public event on Capitol Hill attended by more than 70 people, they shared firsthand accounts of wage theft, union suppression, and gender-based violence and harassment inside Nike’s supply chain. These experiences are not isolated—they are widespread across the garment sector, and continue to be denied by brands that profit from them.

The event also included panelists Oliver Smith of the Communications Workers of America Union (CWA), Abiramy Sivalogananthan of Asia Floor Wage Alliance (AFWA), and Maryam Arain of the Action Center on Race and the Economy (ACRE). Together with the worker activists, they made clear that Nike’s business model depends on exploitation—and that global solidarity is essential to holding the company accountable. Speakers addressed the intersections of labor rights, profit mongering by brands, and U.S. trade policies that sustain the status quo.

The event also included panelists Oliver Smith of the Communications Workers of America Union (CWA), Abiramy Sivalogananthan of Asia Floor Wage Alliance (AFWA), and Maryam Arain of the Action Center on Race and the Economy (ACRE). Together with the worker activists, they made clear that Nike’s business model depends on exploitation—and that global solidarity is essential to holding the company accountable. Speakers addressed the intersections of labor rights, profit mongering by brands, and U.S. trade policies that sustain the status quo.

The Capitol Hill gathering marked a critical moment in the tour—where worker voices moved from factory floors to federal platforms. Leni, Dedeh, and Dinar spoke not only for themselves, but for thousands of women across Asia who demand what they are owed. Their message to policymakers and the public was simple: there are no profits without workers, and there can be no justice without accountability.

The Capitol Hill gathering marked a critical moment in the tour—where worker voices moved from factory floors to federal platforms. Leni, Dedeh, and Dinar spoke not only for themselves, but for thousands of women across Asia who demand what they are owed. Their message to policymakers and the public was simple: there are no profits without workers, and there can be no justice without accountability.

Stay tuned for more updates and read: Day Eight Of The Worker Action Tour | Across Cities, One Fight

Day Eight Of The Worker Action Delegation | Across Cities, One Fight

June 6, 2025Worker Action Delegation

June 2, 2025

After their visit to the site of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire and gathering at Nike’s 5th Avenue store, Dedeh, Leni, and Dinar continued their journey—meeting with union members and more allies who share a commitment to holding brands accountable. In every city, they’ve made it clear: garment workers are organizing across borders, and they are naming the parties responsible for wage theft, union repression, and unsafe working conditions.

In New York City, the delegation met with the NYC Central Labor Council and the Desis Rising Up and Moving (DRUM) organization and visited a memorial quilt exhibit honoring the victims of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire and the Rana Plaza collapse. For the three worker activists, it was a stark reminder that factory disasters don’t happen in isolation—they happen in patterns, when profit is prioritized over people. The memorial connected past and present: the lives lost in New York over a century ago, the lives lost in Rana Plaza and the lives still being risked across global supply chains today.

In New York City, the delegation met with the NYC Central Labor Council and the Desis Rising Up and Moving (DRUM) organization and visited a memorial quilt exhibit honoring the victims of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire and the Rana Plaza collapse. For the three worker activists, it was a stark reminder that factory disasters don’t happen in isolation—they happen in patterns, when profit is prioritized over people. The memorial connected past and present: the lives lost in New York over a century ago, the lives lost in Rana Plaza and the lives still being risked across global supply chains today.

From New York, the workers activists continued to Philadelphia, where they met with more allies, including the Philadelphia Council AFL-CIO, the Philadelphia Coalition of Labor Union Women (CLUW), and the Action Center on Race and the Economy (ACRE). Together, they discussed the ongoing fight to make Nike pay what it owes to garment workers in its supply chain. These meetings were grounded in shared experiences of brand impunity, and in a collective commitment to challenging it through worker and union organizing and cross-border solidarity.

From New York, the workers activists continued to Philadelphia, where they met with more allies, including the Philadelphia Council AFL-CIO, the Philadelphia Coalition of Labor Union Women (CLUW), and the Action Center on Race and the Economy (ACRE). Together, they discussed the ongoing fight to make Nike pay what it owes to garment workers in its supply chain. These meetings were grounded in shared experiences of brand impunity, and in a collective commitment to challenging it through worker and union organizing and cross-border solidarity.

Stay tuned for more updates and read: Day Six Of The Worker Action Tour | Nike, Triangle, and the Women Workers Still Fighting

Day Six Of The Worker Action Delegation | Nike, Triangle, and the Women Workers Still Fighting

June 2, 2025Worker Action Delegation

May 31, 2025

More than a century after 146 workers—most of them young immigrant women—were killed in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire in New York City on 25 March 1911, the same patterns of exploitation continued to persist across continents. The factory fire, which became a pivotal moment for labor rights in the U.S., exposed the deadly consequences of greed, neglect, and the silencing of workers and unions. Factory doors were locked. Fire escapes collapsed. Safety had been sacrificed for profit.

The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire became a national tragedy—but also a catalyst. Outrage over the deaths fueled massive protests and helped spark labor reforms, including stronger fire codes, factory inspections, and the growth of the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union (ILGWU). It was a moment when the lives of women workers—long disregarded—forced their way into the public conscience.

Yet more than a century later, the question lingers: has the world truly changed?

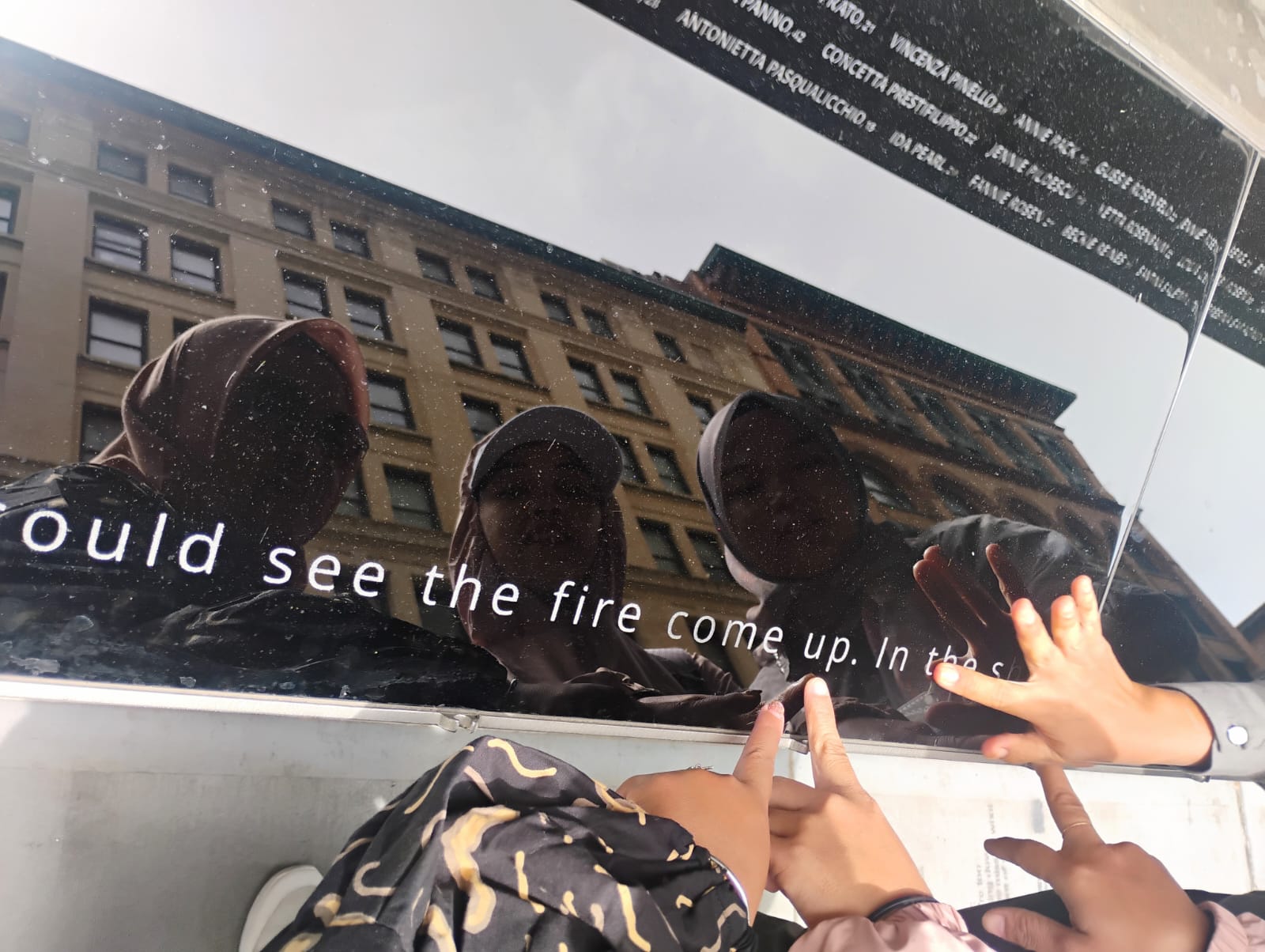

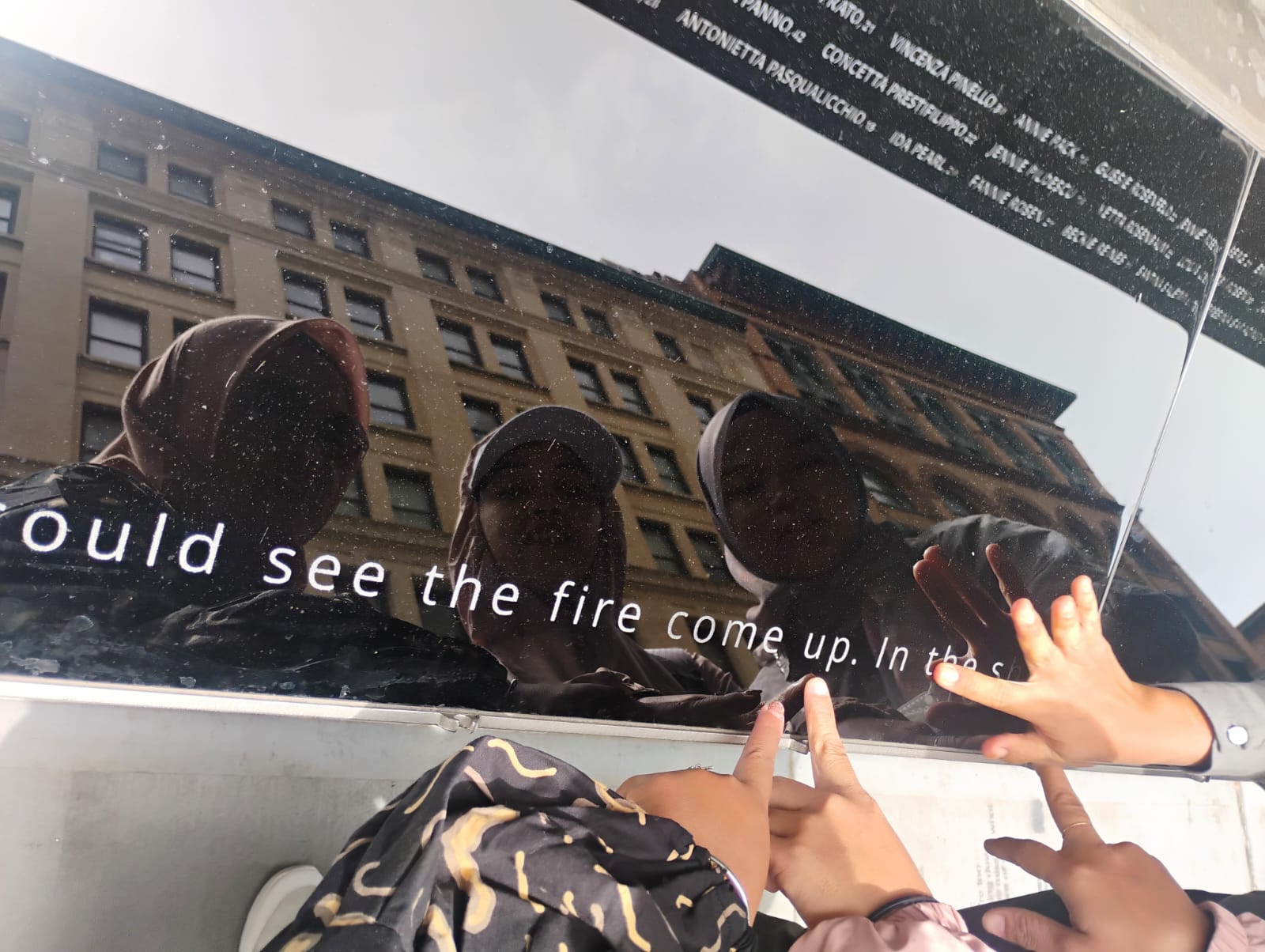

On 31st May, worker activists Dedeh, Dinar, and Leni visited the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire Memorial to honor those lost in the 1911 tragedy. But this visit was not only an act of remembrance—it was a statement. Today, garment workers in Asia, like the three worker activists, face many of the same dangers: poverty wages, union suppression, and production demands that come at the cost of health and safety.

In 1911, the women workers at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, some as young as 15, worked seven days a week, 13-hour shifts, with only a 30-minute lunch break, earning just $6 a week. The conditions were harsh and exploitative. A 114 years later - workers like Dedeh, Leni, and Dinar in Nike’s supply chain face similar challenges. Leni was threatened with dismissal when she took a stand against wages being slashed. Dedeh sometimes had to cover the cost of factory materials herself. Dinar works at breakneck speed to sew Nike logos—60 shoes per hour—while selling coffee and noodles during breaks, and working as a freelance photographer, just to meet basic expenses.

Women garment workers like Dedeh, Leni, and Dinar, who create Nike's products in Indonesia, face a system that still treats them as expendable. During the COVID-19 pandemic, they were laid off, had their wages slashed, or were pushed to resign—while Nike was turning record profits. Their wages today often don’t cover even the cost of the shoes they make.

Outside Nike’s store on 5th Avenue, the worker activists spoke with customers about the realities behind global fashion. In a moment that made those injustices tangible, Leni noticed a customer wearing a pair of shoes she had created. It was a striking reminder that the products made in their factories travel the world, while the women workers who make them remain unseen and unheard. These chance encounters aren’t coincidences—they’re the invisible threads of supply chains and brands that profit from keeping workers hidden.

Outside Nike’s store on 5th Avenue, the worker activists spoke with customers about the realities behind global fashion. In a moment that made those injustices tangible, Leni noticed a customer wearing a pair of shoes she had created. It was a striking reminder that the products made in their factories travel the world, while the women workers who make them remain unseen and unheard. These chance encounters aren’t coincidences—they’re the invisible threads of supply chains and brands that profit from keeping workers hidden.

Their stories echo that of the women workers of Triangle: underpaid, silenced, and asked to sacrifice their safety and well-being for someone else’s bottom line. But like the survivors who marched in protest, the worker activists are not staying quiet. They’re confronting Nike directly—traveling over 8,000 miles to bring their demands to the company’s U.S. headquarters, stores, and even the stadiums built with Nike's profit.

Dedeh, Leni, and Dinar are demanding what is owed. And they are reminding the world: the fire never really stopped. It just moved offshore.

Stay tuned for more updates and read: Day Five Of The Worker Action Tour | Workers Activists File Complaint with Oregon Labor Commissioner

Day Five Of The Worker Action Delegation | Workers Activists File Complaint with Oregon Labor Commissioner

May 31, 2025Worker Action Delegation

May 30, 2025

After being denied a meeting with Nike, three Indonesian worker activists—Dedeh, Dinar, and Leni—found an audience with the Oregon Labor Commissioner Christina Stephenson. The Commissioner kept her office open after-hours to hear firsthand testimony and accept their formal complaint about unpaid wages during the pandemic. “This is part of my struggle to get our rights,” said Leni. “We come here so you can see us—while in our hometown, you never see us.”

In their testimony, the workers described wages as low as $190 a month, grueling production targets that don't leave workers with enough time to access the restroom, and a sexual harassment complaint that took over a year to resolve. They emphasized how Nike’s code of conduct promises dignity and safety—but the reality inside its supplier factories tells a different story. The worker activists also spoke about how the cost of a single pair of Air Jordans often exceeds their monthly pay.

Though Nike did not respond to requests for comment, the workers’ message was loud and clear. As Commissioner Stephenson concluded the meeting, she acknowledged their courage and promised action: “We see you. We appreciate the courage it takes to come here. We’ll take your complaints, and we’ll do what we can.” The labor bureau will now issue a notice of the complaint to Nike and offer the brand a chance to respond.

Stay tuned for more updates and read: Day Four Of The Worker Action Tour | Rename Hayward Field To ‘Hidup Buruh’